- 1Konseptualisasi Kebijaksanaan Modern

- 2Bhagavad Gita

- 3Kebijaksanaan Bhagavad Gita sebagai Konsep Modern

- 4Relevansi Kebijaksanaan pada Psikiatri Modern

- 4..1Metode

- 4..2Referensi

- 5Conceptualization of Modern Wisdom

- 6Bhagavad Gita

- 7Wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita as a Modern Concept

- 8The Relevance of Wisdom to Modern Psychiatry

- 8..1Methods

- 8..2References

Relevansi Kebijaksanaan pada Psikiatri Modern

Psikiatri klinis modern telah dikritik karena kurangnya keberhasilan dalam mempromosikan kesejahteraan pasien meskipun ada langkah besar dalam psikofarmakologi dan psikoterapi berbasis bukti ( Cloniger, 2006 ; Myers dan Diener, 1996). Salah satu kritik terhadap beberapa pendekatan psikoterapi saat ini adalah bahwa pendekatan ini cenderung bersifat reduksionis dan agak bersifat pribadi.

Bhagavad Gita menyarankan pendekatan yang lebih individualistis dan lebih holistik yang dapat mengarah pada pengembangan intervensi psikoterapi yang berfokus pada peningkatan kesejahteraan pribadi daripada hanya gejala kejiwaan. Dua tema utama yang dipromosikan dalam Bhagavad Gita adalah spiritualitas dan pekerjaan. Meskipun perhatian ilmiah yang relatif sedikit diberikan untuk domain ini dalam literatur psikiatrik sebelumnya, data empiris yang dikumpulkan dalam beberapa tahun terakhir menunjukkan pentingnya kedua dimensi ini. Dengan demikian, telah dilaporkan bahwa dokter semakin mengakui hubungan antara kesadaran spiritual yang lebih besar dan hasil yang lebih baik ( D’Souza, 2007 ). Koenig (2007)menemukan bahwa pasien yang lebih tua dengan penyakit medis dan depresi lebih kecil kemungkinannya untuk terlibat secara agama daripada mereka yang tidak depresi serta mereka yang memiliki depresi yang lebih ringan. Demikian pula, pentingnya ‘pekerjaan’ di seluruh umur dan meskipun melumpuhkan penyakit kejiwaan dapat disimpulkan dari penelitian terbaru yang menunjukkan bahwa rehabilitasi kejuruan meningkatkan hasil bahkan pada orang tua dengan skizofrenia yang sangat kronis ( Twamley et.al., 2005). Sastra di daerah-daerah ini dan lainnya yang terkait dengan berbagai dimensi kebijaksanaan tumbuh, tetapi tetap tersebar dan tidak terhubung. Mengevaluasi studi-studi ini melalui paradigma kebijaksanaan dapat menunjuk ke hubungan-hubungan baru di antara konsep-konsep pekerjaan, spiritualitas, kesejahteraan, dan hasil-hasil yang sukses. Ini juga bisa menjadi dasar untuk merancang intervensi yang mempromosikan kesejahteraan yang lebih luas seperti yang disarankan oleh Cloninger (2006).

Studi kebijaksanaan tampaknya memiliki relevansi yang cukup besar untuk psikiatri. Walaupun mungkin sulit untuk mengembangkan intervensi yang bertujuan mempromosikan konstruksi multi-dimensi seperti kebijaksanaan, masuk akal untuk menyarankan bahwa intervensi yang ditujukan untuk meningkatkan dimensi kebijaksanaan tertentu dapat meningkatkan hasil pada orang yang sakit mental. Konsep kebijaksanaan memang dapat bermanfaat bagi psikiatri sebagai ‘payung’ di mana beberapa pendekatan baru untuk meningkatkan hasil pada orang-orang yang sakit mental dapat dikelompokkan dan dan digunakan sebagai landasan untuk menciptakan model remisi dan pemulihan yang terintegrasi.

Akhirnya, studi perbandingan lintas-budaya dari konsep kebijaksanaan akan sangat membantu, karena mereka mungkin memiliki implikasi untuk mengembangkan intervensi yang mungkin untuk meningkatkan kebijaksanaan sebagai sarana memfasilitasi penuaan yang berhasil dalam cara budaya tertentu. Selain itu, menggabungkan unsur-unsur kebijaksanaan dari berbagai budaya dapat menghasilkan cara yang lebih komprehensif dan efektif untuk mempromosikan kebijaksanaan.

Metode

Untuk memeriksa konsep kebijaksanaan sebagaimana diuraikan dalam Bhagavad Gita, kami melakukan tinjauan independen untuk masing-masing dari dua terjemahan bahasa Inggris utama. Kami meninjau terjemahan langsung teks Sanskerta Bhagavad Gita daripada komentar ilmiah karena kami merasa bahwa komentar tersebut akan bias oleh pendapat subjektif dari para komentator. Kami memilih terjemahan oleh RC Zaehner (orang barat dengan beasiswa dalam bahasa Sanskerta) yang direvisi dan diedit oleh Goodall (1996) , dan yang lain oleh Swami Nirmalananda Giri (2007), seorang sarjana Hindu India.

Keuntungan tambahan dari terjemahan yang terakhir adalah bahwa terjemahan ini juga tersedia dalam format elektronik, memungkinkan kami untuk menganalisis teksnya menggunakan perangkat lunak elektronik. Ada beberapa perbedaan dalam tata bahasa dan sintaksis antara terjemahan Zaehner dan Giri; Namun, variasi tersebut tidak terlihat memiliki dampak signifikan pada makna penting dari teks yang disampaikan.

Untuk mengukur kepentingan relatif dari masing-masing domain seperti yang dijelaskan dalam Bhagavad Gita, kami melakukan analisis terhadap teks versi elektronik Giri terjemahan menggunakan QSR NVivo ( Fraser, 2000 ), Versi 2.0, yang merupakan perangkat lunak yang dirancang untuk memfasilitasi analisis teks kualitatif / kuantitatif campuran. Kami menggunakan metode “Coding Consensus, dan Perbandingan”. Dalam beberapa kasus, ayat yang sama dapat diberikan lebih dari satu kode atau domain.

Untuk memvalidasi penggunaan kata-kata bahasa Inggris kami untuk menjelaskan konsep yang awalnya disampaikan dalam bahasa Sanskerta, kami menggunakan metode terjemahan terbalik. Awalnya kami menggunakan Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon (2006) untuk menghasilkan daftar sinonim bahasa Sansekerta untuk kata ‘wisdom’, ‘wise’ dan ‘sage’. Selanjutnya, kami menggunakan sumber daya online yang disediakan oleh Bhagavad-Gita Trust (1998), yang memungkinkan kami untuk membandingkan setiap ayat teks dalam bahasa Inggris dan Sanskerta secara bersamaan. Dengan ini, kami membuat daftar kata yang digunakan dalam teks Sanskerta Bhagavad Gita yang diterjemahkan sebagai ‘kebijaksanaan’, ‘bijaksana’ atau ‘bijak’ dalam versi bahasa Inggris yang digunakan dalam analisis asli kami. Daftar ini kemudian dibandingkan dengan daftar sinonim yang diperoleh dengan menggunakan leksikon Sanskerta Cologne. Kami menemukan kecocokan 100% antara daftar kata-kata Sansekerta yang digunakan dalam Gita dan daftar sinonim untuk kata kunci tersebut.

Setelah kami mengkodekan terjemahan elektronik, kami membandingkannya dengan terjemahan Zaehner ( Goodall, 1996). Ada kecocokan 100% antara kedua terjemahan dalam hal domain tertentu yang dicakup oleh masing-masing ayat, meskipun ada perbedaan kecil dalam urutan penggunaan kata, sintaksis, dan tata bahasa. Frekuensi ayat-ayat yang menentukan wilayah kebijaksanaan tertentu kemudian dihitung. 10 domain yang kami identifikasi (dengan jumlah ayat yang terkait dengan setiap domain yang diberikan dalam tanda kurung) adalah sebagai berikut: Pengetahuan kehidupan (28 ayat), Peraturan Emosional (20 ayat), Kontrol atas Keinginan (20 ayat), Ketegasan (20 ayat) ), Cinta Tuhan (19 ayat), Tugas dan Kerja (14 ayat), Yoga atau Integrasi Kepribadian (12 ayat), Welas Asih / Pengorbanan (8 ayat), dan Wawasan / Kerendahan Hati (7) ayat).

Referensi

- Ardelt M. Wisdom as expert knowledge system: a critical review of a contemporary operationalization of an ancient concept. Human Development. 2004;47:257–285.

- Assmann A. Life-span development and behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum;

- Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. Wholesome knowledge: Concepts of wisdom in a historical and cross-cultural perspective. Avari B. India: The Ancient Past. Routledge; London: 2007.

- Baltes PB, Gluck J, Kunzmann U. Wisdom: Its structure and function in regulating successful lifespan development. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. Vol. 347. Oxford University Press; London: 2002. p. 327.

- Baltes PB, Smith J, Staudinger UM. Wisdom and successful aging. In: Sonderegger T, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln: 1992.

- Baltes PB, Staudinger UM. Wisdom: a metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. American Psychologist. 2000;55:122–136.

- Easwaran E. The Bhagavad Gita. Nilgiri Press; Tomales, CA: 1985.

- Erikson EH. Identity and the Life Cycle. International University Press; New York: 1959.

- Gambhirananda S. Bhagawad-Gita. Sixth Impression; Kolkata, India: 2003.

- Gandhi MK. Young India. 1925. pp. 1078–1079.

- Miller BS, Moser B. The Bhagavad-Gita: Krishna’s Counsel in Time of War. Columbia University Press; New York: 1986.

- Munshi KM. Bhagavad Gita and Modern Life. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan; Mumbai, India: 1962.

- Robinson CA. Interpretations Of The Bhagavad-Gita And Images Of The Hindu Tradition: The Song Of The Lord. Routledge; London: 2005a.

- Sargeant W. The Bhagavad Gita. State University of New York Press; Albany, NY: 1994.

- Steiner R. Bhagavad Gita and the West. Rudolf Steiner Press; London: 2007.

- Sternberg RJ. A Balance Theory of Wisdom. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:347–365.

- Vivekananda S. Bhakti Yoga. Leeds, England: 2003.

- Witzel M. The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2003. Vedas and Upanishads.

[:en]This article focuses on the conceptualization of wisdom in the Bhagavad Gita, arguably the most influential of all ancient Hindu philosophical texts. Our review, using mixed qualitative/quantitative methodology with the help of Textalyser and NVivo software, found the following components to be associated with the concept of wisdom in the Gita: Knowledge of life, Emotional Regulation, Control over Desires, Decisiveness, Love of God, Duty, and Work, Self-Contentedness, Compassion/Sacrifice, Insight/Humility, and Yoga (Integration of personality). A comparison of the conceptualization of wisdom in the Gita with that in modern scientific literature shows several similarities, such as rich knowledge about life, emotional regulation, insight, and a focus on the common good (compassion). Apparent differences include an emphasis in the Gita on control over desires and renunciation of materialistic pleasures. Importantly, the Gita suggests that at least certain components of wisdom can be taught and learned. We believe that the concepts of wisdom in the Gita are relevant to modern psychiatry in helping develop psychotherapeutic interventions that could be more individualistic and more holistic than those commonly practiced today, and aimed at improving personal well-being rather than just psychiatric symptoms.

The study of wisdom has become a subject of increasing scientific interest and inquiry over the past three decades, although the concept of wisdom is probably an ancient one (Ardelt, 2004; Baltes and Staudinger, 2000; Brugman, 2006; Robinson, 2005a). It has been suggested that modern conceptualization of wisdom and its domains is derived largely from concepts described in classical Greek philosophy (Brugman, 2006). Recent work, primarily in the fields of gerontology, psychology, and sociology, has focused largely on defining wisdom and identifying its domains. Indicative of the growing popularity of this topic, a recent article in the Sunday supplement of the New York Times was devoted to wisdom (Hall, 2007).

We believe that the topic of wisdom should be of interest to the field of psychiatry too. This would include cross-cultural psychiatry as well as prevention and intervention in the area of successful aging. Vaillant (2002) considers wisdom to be an integral part of successful aging, although he believes that one need not be old to acquire/possess wisdom. Blazer (2006) has proposed that the promotion of wisdom should be an important part of facilitating successful aging, although evidence-based techniques or tools to affect wisdom are not available at this time. As the empirical study of wisdom is present in its nascent stages there may be an opportunity to incorporate culture-specific elements in our definition and understanding of this elusive concept, and thereby position ourselves to design possible “interventions” to help enhance wisdom in culturally appropriate ways.

Hindu philosophy is considered to be among the oldest schools of philosophy (Flood, 1996). Its exact origins are difficult to trace as written Indian philosophy is believed to be predated by centuries of an oral tradition (Avari, 2007; Bryant, 2001). The Vedas are the oldest of the ancient Hindu texts and have been dated to the second millennium BC (Witzel, 2003). These were written in Sanskrit; however, the oral Vedic tradition has been dated back as far as 10,000 BC (Sidharth, 1999).

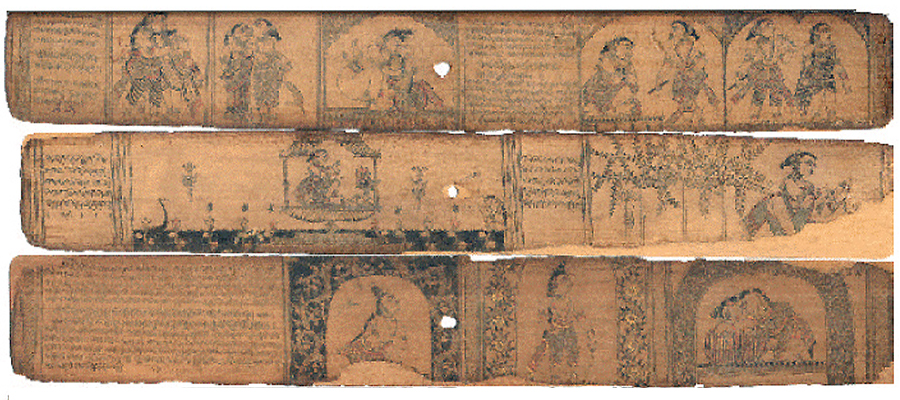

In this article, our aim is to examine similarities and differences between the concepts of wisdom in modern western versus ancient Indian literature. We see this as a useful first step in improving our understanding of wisdom. We focus on the Bhagavad Gita, commonly referred to as the Gita. The Gita is a later Hindu text than the Vedas and is regarded by many scholars of Hinduism as a distillation of key Vedic concepts (Robinson, 2005a; Miller and Moser, 1986; Easwaran, 1985). It is arguably the most influential of all Hindu philosophical/religious texts (Easwaran, 1985), and is thought to provide a practical guide to the implementation of Vedic wisdom in day-to-day life (Rosen, 2006). Large sections of the four primary Vedas (Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda, and Atharva Veda), as well as the other Vedic texts (Upanishads, Aranyakas, Puranas), include hymns, religious rituals, sacrificial rites, incantations, and some treatises on medicine (Goodall, 1996). Therefore, the Gita is a more practical document than the Vedas for the purposes of interpreting the conceptualization of wisdom in ancient Hindu literature.

It is important to note that in its original form, the Gita is a religious text. Several verses in the text deal with topics related to devotion and interactions with God/the Divine. However, in addition to its religious/spiritual message, the Gita also has a broader and more secular dimension, and, as described below, its principles have been applied by scholars to a variety of non-religious endeavors as well (Sargeant, 1994; Sharma, 1999; Robinson, 2005a; Hall, 2007; Business week, 2007).

We should add that we do not claim to be scholars of the Hindu religion nor of Sanskrit language, but have some knowledge of both. This paper is not meant to be a general discourse or commentary on the Gita or on the Hindu philosophy or religion. Rather, we review the Gita as a source text for understanding ancient Hindu conceptualization of wisdom. We used a mixed qualitative and quantitative methodology with the help of Textalyser and NVivo software to determine the domains specifically linked to wisdom in the Gita. Below, we first summarize the major modern views on wisdom, then describe the conceptualization of wisdom in the Gita, and finally, narrate similarities and differences between these two.

Conceptualization of Modern Wisdom

Modern conceptualization of wisdom is thought to be derived mainly from the Greek philosophy (Brugman, 2006), especially the writings of Socrates (469 – 399 BC) (Kofman, 1998), Plato (427 – 340s BC) (Hare, 1982), and Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) (Ross, 2004). Recent research on wisdom has focused more on theoretical aspects and definitions of wisdom than on empirical studies. There is no single consensual definition of wisdom, although there are several commonly identified elements. Erikson (1959) was one of the first psychologists to address wisdom as an important component of personality development. He designated wisdom as a successful outcome of late-life development; however, he did not provide explicit definitions or constructs of wisdom. Baltes, probably the most prolific contemporary wisdom researcher, has referred to wisdom as the pinnacle of human achievement (Baltes and Staudinger, 2000; Baltes, Gluck, and Kunzmann, 2002; Baltes and Kunzmann, 2003; Baltes, Staudinger, Maercker, and Smith, 1995). The Berlin Wisdom paradigm constructed by Baltes and colleagues (Baltes and Staudinger, 2000; Baltes et al., 2002; Baltes and Kunzmann, 2003; Baltes et al., 1995; Baltes, Smith, and Staudinger, 1992; Baltes, 2003) constitutes the most comprehensive work done in this area. It conceives wisdom as “expertise in the pragmatics of life, serving the good of oneself and others”. Baltes used a collection of 5 criteria (2 basics and 3 meta-criteria) to assess wisdom-related performance – rich factual knowledge, rich procedural knowledge, lifespan contextualism, relativism of values, exceptional insight, and management of uncertainty. Based on studies using these criteria, Baltes and colleagues concluded that wisdom was a rare quality (Baltes and Staudinger, 2000). Another prominent theory of wisdom is Sternberg’s balance theory (Brugman, 2006; Sternberg, 1998). In this view, a high level of practical intelligence (common sense) is the basis of wisdom and is used to balance multiple factors and interests (intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal) for the sake of common good. The Berlin Paradigm and the balance theory are referred to as the pragmatic theories. Complementing the pragmatic theories are the epistemic theories of wisdom, such as Brugman’s wisdom model (Brugman, 2006), which emphasizes limitations of human knowledge, and the core of such models is an acknowledgment of uncertainty. They stress attitude toward knowledge, openness to new experience, and adaptability in the face of uncertainty.

Recent work by Ardelt (2004) and Carstensen (2006) emphasizes the role of emotional regulation. Ardelt (2004) believes that wisdom is better conceptualized as integration of cognitive, reflective, and affective personality domains rather than just possession and implementation of expert knowledge as proposed in the Berlin paradigm. Carstensen (2006) has sought to integrate the domains of cognitive aging and socioemotional aging from the perspective of a motivational theory of lifespan development, although she does not use the term wisdom. Jason et al. (2001) incorporate harmony and warmth as well as spiritual elements and mysticism in the definition of wisdom. In summary, wisdom is a multidimensional construct, and there is a general agreement on several, though not all, of the domains involved. The domains common to a number of the modern theories of wisdom include rich knowledge of life, emotional regulation, acknowledgment of and appropriate action in the face of uncertainty, personal well being, helping common good, and insight.