Determinisme Ilmu Pengetahuan

Sebagian besar filsuf setuju bahwa apakah determinisme itu benar atau tidak, adalah masalah kontingen; yaitu, determinisme tidak harus benar atau salah. Jika demikian, maka apakah determinisme benar atau tidak menjadi masalah empiris, yang dapat ditemukan dengan menyelidiki cara dunia ini, bukan melalui argumentasi filosofis. Ini bukan untuk menyangkal bahwa kebenaran determinisme akan memiliki implikasi metafisik. Untuk satu, kebenaran determinisme akan mensyaratkan bahwa hukum-hukum alam tidak hanya probabilistik – karena jika ya, maka konjungsi dari masa lalu dan hukum-hukum tidak akan memerlukan masa depan yang unik. Lebih jauh, seperti yang akan kita lihat, para filsuf sangat peduli tentang apa implikasi kebenaran determinisme terhadap kehendak bebas. Tetapi poin yang perlu diperhatikan adalah bahwa jika kebenaran determinisme adalah kebenaran kontingen tentang bagaimana dunia sebenarnya, maka penyelidikan ilmiah harus memberi kita wawasan tentang masalah ini. Mari kita katakan bahwa dunia yang mungkin adalah deterministik jika determinisme kausal benar di dunia itu. Ada dua cara dunia gagal untuk menjadi deterministik.

Bagian-bagian tertentu dari fisika memberi kita alasan untuk meragukan kebenaran determinisme. Sebagai contoh, interpretasi standar Teori Kuantum, Interpretasi Kopenhagen, menyatakan bahwa hukum yang mengatur sifat bersifat indeterministik dan probabilistik. Menurut interpretasi ini, apakah partikel kecil seperti quark membelok ke arah tertentu pada waktu tertentu dijelaskan dengan benar hanya dengan persamaan probabilistik. Meskipun persamaan dapat memprediksi kemungkinan bahwa quark berbelok ke kiri pada waktu tertentu, apakah itu benar-benar berbelok atau tidak bersifat indeterministik atau acak.

Ada juga interpretasi deterministik dari Teori Quantum, seperti Interpretasi Banyak-Dunia. Untungnya, hasil dari perdebatan mengenai apakah Teori Kuantum paling tepat ditafsirkan secara deterministik atau tidak pasti, sebagian besar dapat dihindari untuk tujuan kita saat ini. Sekalipun sistem partikel mikro seperti quark tidak dapat ditentukan, mungkin saja sistem yang melibatkan objek fisik yang lebih besar seperti mobil, anjing, dan manusia bersifat deterministik. Ada kemungkinan bahwa satu-satunya ketidakpastian adalah pada skala partikel mikro dan bahwa objek makro itu sendiri mematuhi hukum deterministik. Jika ini masalahnya, maka determinisme kausal seperti yang didefinisikan di atas, sebenarnya, salah, tetapi “hampir” benar. Artinya, kita bisa mengganti determinisme dengan “determinisme dekat,”

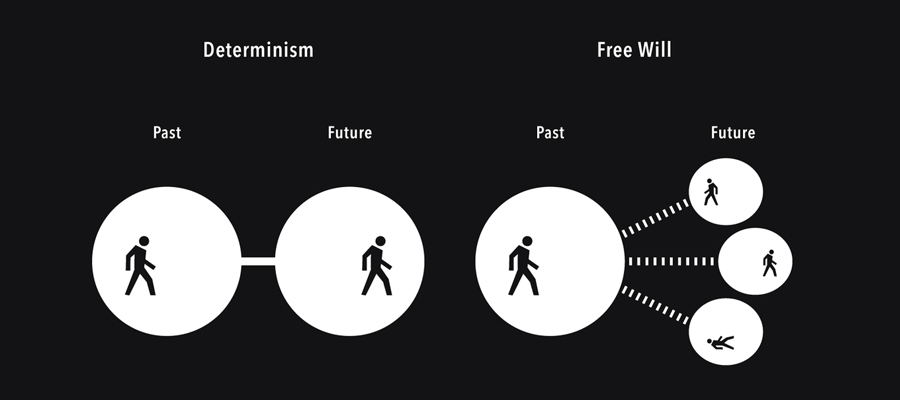

Bisakah kita memiliki kehendak bebas bahkan jika determinisme benar?

Adalah cara yang bermanfaat untuk membedakan posisi utama mengenai kehendak bebas. Ahli kompatibilitas menjawab pertanyaan ini dalam persetujuan. Mereka percaya bahwa seorang dapat memiliki kehendak bebas bahkan jika determinisme kausal itu benar atau bahkan jika determinisme dekat itu benar. Dalam hal berikut, saya akan menghilangkan kualifikasi ini.

Dengan kata lain, keberadaan kehendak bebas di dunia yang mungkin kompatibel dengan dunia yang deterministik. Karena alasan ini, posisi ini dikenal sebagai “compatibilism,” dan para pendukungnya disebut “compatibilists.” Menurut ahli compatibilist, adalah mungkin bagi seorang untuk ditentukan dalam semua pilihan dan tindakannya dan masih membuat beberapa pilihannya dengan bebas.

Menurut “inkompatibilis”, keberadaan kehendak bebas tidak sesuai dengan kebenaran determinisme. Jika dunia tertentu yang diberikan bersifat deterministik, maka tidak ada agen di dunia itu yang memiliki kehendak bebas karena alasan itu. Lebih jauh, jika seseorang berasumsi bahwa memiliki kehendak bebas adalah syarat yang diperlukan untuk bertanggung jawab secara moral atas tindakan seseorang, maka ketidakcocokan kehendak bebas dan determinisme akan menyebabkan ketidakcocokan tanggung jawab moral dan determinisme kausal.

Setidaknya ada dua jenis inkompatibilis. Beberapa inkompatibilis berpikir bahwa determinisme adalah benar dari dunia nyata, dan dengan demikian tidak ada agen di dunia nyata yang memiliki kehendak bebas. Inkompatibilis seperti itu sering disebut “determinis keras” [lihat Pereboom (2001) untuk pembelaan determinisme keras]. Para inkompatibilis lain berpendapat bahwa dunia yang sebenarnya tidak deterministik dan bahwa setidaknya beberapa agen di dunia yang sebenarnya memiliki kehendak bebas. Ini inkompatibilis disebut sebagai “libertarian” [lihat Kane (2005), khususnya bab 3 dan 4]. Namun, kedua posisi ini tidak lengkap. Ada kemungkinan bahwa seseorang adalah inkompatibilis, berpikir bahwa dunia yang sebenarnya tidak deterministik, namun masih berpikir bahwa agen di dunia yang sebenarnya tidak memiliki kehendak bebas. Meskipun kurang jelas apa yang disebut posisi seperti itu (mungkin “kehendak bebas mendustakan”), itu menggambarkan bahwa determinisme keras dan libertarianisme tidak melelahkan cara untuk menjadi inkompatibilis. Karena semua inkompatibilis, apa pun garis mereka, setuju bahwa kepalsuan determinisme adalah syarat yang diperlukan untuk kehendak bebas, dan karena kompatibilis menyangkal pernyataan ini, bagian berikut berbicara tentang inkompatibilis dan kompatibilis.

Penting juga untuk diingat bahwa baik kompatibilitas maupun ketidakcocokan adalah klaim tentang kemungkinan. Menurut ahli compatibilis, ada kemungkinan bahwa agen sepenuhnya ditentukan dan belum bebas. Sebaliknya, inkompatibilis berpendapat bahwa keadaan semacam itu mustahil. Tetapi tidak satu pun posisi dengan sendirinya membuat klaim tentang apakah agen benar-benar memiliki kehendak bebas atau tidak.

Jika kebenaran determinisme adalah masalah kontingen, maka apakah agen bertanggung jawab secara moral atau tidak akan tergantung pada apakah dunia aktual itu deterministik atau tidak. Lebih jauh lagi, bahkan jika dunia yang sebenarnya tidak pasti, itu tidak segera mengikuti bahwa ketidakpastian yang ada sekarang adalah jenis yang diperlukan untuk kehendak bebas.

Para inkompatibilis mengatakan bahwa kehendak bebas tidak sesuai dengan kebenaran determinisme. Tidak semua argumen untuk inkompatibilisme dapat dipertimbangkan di sini; mari kita fokus pada dua varietas utama. Variasi pertama dibangun di sekitar gagasan bahwa memiliki kehendak bebas adalah masalah memiliki pilihan tentang tindakan tertentu kita, dan bahwa memiliki pilihan adalah masalah memiliki pilihan asli atau alternatif tentang apa yang dilakukan seseorang. Berbagai argumen kedua dibangun di sekitar gagasan bahwa kebenaran determinisme akan berarti bahwa kita tidak menyebabkan tindakan kita dengan cara yang benar. Kebenaran determinisme akan berarti bahwa kita tidak memulai tindakan kita dengan cara yang signifikan dan tindakan kita pada akhirnya tidak dikendalikan oleh kita. Dengan kata lain, kita tidak memiliki kemampuan untuk menentukan nasib sendiri.

Referensi

- Finch, Alicia and Ted Warfield (1998). “The Mind Argument and Libertarianism”.

- Fischer, John Martin (1984). “Power Over the Past,” Pacific Philosophical Quarterly.

- Descartes, René (1998). Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy, 4th edition (Hackett Publishing Company).

- Frankfurt, Harry (1971). “Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person,” reprinted in Pereboom (1997)

- Helm, Paul (1994). The Providence of God (InterVarsity Press).

- Kane, Robert (1998). The Significance of Free Will (Oxford University Press).

- Lewis, David (1981). “Are We Free to Break the Laws?” Theoria 47: 113-121.

- O’Connor, Timothy (2000). Persons and Causes: The Metaphysics of Free Will (Oxford University Press).

- Pereboom, Derk (2001). Living Without Free Will (Cambridge University Press).

- Smilansky, Saul (2000). Free Will and Illusion (Clarendon Press).

- Strawson, Galen (1994). “The Impossibility of Moral Responsibility,” Philosophical Studies.

- Van Inwagen, Peter (1983). An Essay on Free Will (Clarendon Press).

[:en]Most of us are certain that we have free will, though what exactly this amounts to is much less certain. According to David Hume, the question of the nature of free will is “the most contentious question of metaphysics.” If this is correct, then figuring out what free will is will be no small task indeed. Minimally, to say that an agent has free will is to say that the agent has the capacity to choose his or her course of action.

But animals seem to satisfy this criterion, and we typically think that only persons, and not animals, have free will. Let us then understand free will as the capacity unique to persons that allows them to control their actions. It is controversial whether this minimal understanding of what it means to have a free will actually require an agent to have a specific faculty of will, whether the term “free will” is simply shorthand for other features of persons, and whether there really is such a thing as free will at all.

This article considers why we should care about free will and how freedom will relate to freedom of action. It canvasses a number of the dominant accounts of what the will is, and then explores the persistent question of the relationship between free will and causal determinism, articulating a number of different positions one might take on the issue. For example, does determinism imply that there is no free will, as the incompatibilists argue, or does it allow for free will, as the compatibilists argue? This article explores several influential arguments that have been given in favor of these two dominant positions on the relationship between free will and causal determinism. Finally, there is a brief examination of how free will relates to theological determinism and logical determinism.

Free Will, Free Action and Moral Responsibility

We most often think that an agent’s free actions are those actions that she does as a result of exercising her free will.

Freedom consists of no external obstacles to a person who does what he wants.

A free person is he who can do what he wants and be patient as he pleases.

Freedom is the absence of external obstacles.

In Questions Regarding Human Understanding, that free will is simply “the power of action or inaction, according to the will of the will: that is if we choose to remain silent; if we can also choose to move. Freedom is only the ability to choose actions, and an agent must free if he is not prevented by some external obstacles to complete the action.

Whether a person can have freedom of action without free will depends on one’s view of what free will is. Also, the truth of causal determinism will not require that agents do not have the freedom to do what they want to do. An agent can do what he wants to do, even if he is determined to do it. As such it is precisely categorized as a compatible person.

Even if there is a difference between free will and freedom of action, it seems that free will is necessary for the implementation of free action.

Another reason for caring about free will is that it seems necessary for moral responsibility. While there are various stories about what moral responsibility really is, it is widely agreed that moral responsibility is different from causal responsibility.

Depending on one’s cause and effect account, it is also possible to be morally responsible for an event or condition, even if a person is not responsible for the same event or condition. For the current purpose, let us say that an agent is morally responsible for an event or condition only if he is the recipient of moral praise or moral error that is appropriate for the event or condition. According to the view of the relationship between free will and moral responsibility, if the agent does not have free will, then the agent is not morally responsible for his actions.

Some philosophers do not believe that free will is needed for moral responsibility. According to John Martin Fischer, humans do not have free will, but they are morally responsible for their choices and actions. In short, the type of control needed for moral responsibility is weaker than the type of control needed for free will. Furthermore, the truth of causal determinism will hinder the type of control needed for free will, but it will not hinder the type of control needed for moral responsibility.

However, many think that the importance of free will is not limited to the need for free action and moral responsibility. Philosophers assert that free will is also a requirement for agency, rationality, autonomy, and dignity of people, creativity, cooperation, and the value of friendship and love. Thus we see that free will is the center of many philosophical problems.

Will Model

The model of will has origins in the writings of ancient philosophers, and that is the dominant view of desire in the middle ages and modern philosophy. Still has a lot of supporters in contemporary literature. What is different from free agents, according to this model, is their ownership of certain powers or capacities. All living things have several capacities, such as the capacity for growth and reproduction. However, what is unique about free agents is that they also have the capacity to think and be willing. Another way of saying this is that free agents themselves have intellectual abilities and wills. It is a virtue to have these additional faculties, and the interaction between them, that agents have free will.

Intellect, or rational ability, is the power of cognition. As a result of cognitive, intellect presents various things as you wish with an explanation. Furthermore, all agents who have intelligence also have the will. Desire, or state of will, is the desire for good; that is, he is naturally attracted to goodness. Therefore, the will cannot pursue the choices presented by the intellect as a good thing. The will can command the body to move or the intellect to consider something.

A person who has intelligence can act with free judgment, as long as he understands the general tone of goodness; from which he can judge this or other things to be good. As a result, wherever there is intelligence, there is free will.

Through the interaction between intellect and will, a person has the free will to pursue something that he considers good.

Hierarchical of Will

Not all desires produce physical actions. Even if someone has conflicting desires, then it is impossible for someone to satisfy all their desires. Such effective desires are called volition; volition is the desire that moves a person to physical action. Likewise, one can distinguish between mere second-order desires (only desires to have certain desires) and second desires (desires for desires to be one’s will, or desires for desires to become desires).

According to the view of the will hierarchy, free will consists of having a volume of orders. In other words, a person has free will if he can have the type of desire he wants. A person acts of his own free will if his actions are the result of the desire of the first order that he wants to be the desire of the first order.

The treatment of freedom will take as a starting point the claim that a person involves sensitivity to certain reasons. A person acts with free will if he is responsive to appropriate rational considerations, and he does not act with free will if he is less responsive like that.